Native American facts regarding Screven County and the State of Georgia

screven County, located in the Coastal Plain of Georgia, was created on December 14, 1793, as the state's fourteenth county. It was named for General James Screven, who served as a commander in Savannah during the Revolutionary War (1775-83) and was a veteran of the Battle of the Riceboats. The county was carved out of the lower part of Burke County and the upper part of Effingham County, and originally included Bulloch County and parts of Emanuel and Jenkins counties. Rocky Ford was designated as the first county seat in 1793 but was replaced by Jacksonborough in 1797

The original inhabitants of the area were Yuchi Indians. The first European settlers of Screven County were Germans who arrived in 1751. They were followed two years later by native-born American settlers who came mainly from the Carolinas and Virginia. In 1763, at the Southern Indian District Congress in Augusta, the Indians ceded the land between the Savannah River and the Ogeechee River. When the American Revolution began, what would later become Screven County was divided between St. Mathew Parish and St. George Parish.

The BIA requires Native Americans to prove their genealogical descent from listed members of historical Indian tribes in 1900. However, until the early 1970s it was not legal for Indians to live in Alabama and Georgia. Native Americans were given two options by census takers. They could say that they were either “white” or “colored.” Thus, American Indians were officially extinct in Alabama and Georgia until the 1970s. It would be impossible for a citizen of either of these states to claim Federal status, since by official definition, no Indians lived in these states after 1843, which was when Federal troops were last used to evict Creek Indians in Georgia.

Fabricated history and inaccurate maps

Throughout the first half of the 18th century, the Muskogean tribes of what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama traded with both the English and French, but preferred the company of the

French, who treated them with much more respect. During the French & Indian War (1754-1763) most of the tribes in this region stayed loyal to France and fought the allies of the British.

The Colony of South Carolina promised the Cherokees all of the lands in Tennessee and Alabama occupied by France's Indian allies, if the Cherokees would send warriors to fight Canadian Indians. The

Colony of Georgia promised the Georgia Creeks all of the land of the allies of the French, if they would just stop burning Cherokee towns! In 1715 the Cherokees had killed all the Creek leaders in

their sleep while attending a diplomatic conference in Tugaloo, then stolen a huge chunk of Creek territory in the North Carolina mountains. The Creeks had been trying to annihilate the Cherokees

ever since then.

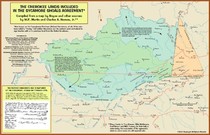

In 1757 the Cherokees changed sides from the British to the French, then attacked the frontier colonies. Armies from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and the Creeks, of course, then invaded the heart of the Cherokee Nation. Great Britain took back the vast territory that it had promised the Cherokees as punishment. Unfortunately, the 1754 map created by the British to bribe the Cherokees has become the map used by the U. S, Department of the Interior for determining ethinic boundaries in the Southeast. As a result, the Official United States Government Map does not show the true original territories of five federally recognized tribes and 14 state recognized tribes in the Southeast.

The war damage was devastating to the Cherokees. Most of their towns were destroyed by either Creek allies of the British in 1754, Creek allies of the French in 1755, or the colonial militia's between 1757 and 1763. At the conclusion of the war, many of the Muskogean towns, who had been allied with the French, left Alabama. Creek towns from South Carolina and Georgia took their place in much of what would become the State of Alabama. The Choctaws continued to live in western Alabama along with some Alabama tribal towns. The Cherokees were awarded northeastern Alabama and northwestern Georgia, while losing most of their land in the Carolinas as punishment for changing sides. The Cherokees were also given the Yuchi’s and Chickasaw’s lands in eastern Tennessee. However, the Chickasaws continued to occupy some villages in what is now northern Georgia, southwest Georgia and northwestern Alabama.

Almost all official maps of the Southeastern Indian tribes today describe a hypothetical world drawn by British Colonial Office bureaucrats in 1763 that never existed. Until 1763, the Alabama tribe was the dominant ethnic group in Alabama. After 1763 British colonial maps showed all of what would become the State of Alabama occupied by either the Creek Indians or the Cherokee Indians. In the eyes of British, and later, American officials, the Alabama, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Shawnee, Tawasee (Arawak,) Yuchi and Apalachicola Indians of Alabama were officially extinct.

Founding of Georgia Colony

When, in 1729, the proprietors of the Carolinas surrendered their charter to the crown, the whole country southward of the Savannah River to the vicinity of St. Augustine was a wilderness, peopled by native tribes, and was claimed by the Spaniards as a part ofFlorida. The English disputed the claim, and war clouds seemed to be gathering. At that juncture GENERAL JAMES EDWARD OGLETHORPE, commiserating the wretched condition of prisoners for debt who crowded the English prisons, proposed in Parliament the founding of a colony in America, partly for the benefit of this unfortunate class, and as an asylum for oppressed Protestants of Germany and other Continental states. A committee of inquiry reported favorably, and the plan, as proposed by Oglethorpe, was approved by King George II. A royal charter was obtained for a corporation (June 9, 1732) for twenty-one years, " in trust for the poor," to establish a colony in the disputed territory south of the Savannah, to be called Georgia, in honor of the King. Individuals subscribed largely to defray the expenses of emigrants, and within two years Parliament appropriated $160,000 for the same purpose. The trustees, appointed by the crown, possessed all legislative and executive power, and there was no political liberty for the people. In November, 1732, Oglethorpe left England with 120 emigrants, and, after a passage of fifty days, touched at Charleston, giving great joy to the inhabitants, for he was about to erect a barrier between them and the Indians and Spaniards. Landing a large portion of the emigrants on Port Royal Island, he proceeded to the Savannah River with the remainder, and upon Yamacraw Bluff (the site of Savannah) he laid the foundations of the future State in the ensuing spring of 1733. The rest of the emigrants soon joined him. They built a fort, and called the place Savannah, the Indian name of the river, and there he held a friendly conference with the Indians, with whom satisfactory arrangements for obtaining sovereignty of the domain were made. Within eight years 2,500 emigrants were sent over from England at an expense to the trustees of $400,000.

The condition upon which the lands were parcelled out was military duty; and so grievous were the restrictions, that many colonists went into South Carolina, where they could obtain land in fee. Nevertheless, the colony increased in numbers, a great many emigrants coming from Scotland and Germany. Oglethorpe went to England in 1734, and returned in 1736 with 300 emigrants, among them 150 Highlanders skilled in military affairs. John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield came to spread the gospel among the people and the surrounding natives. Moravians had also settled in Georgia, but the little colony was threatened with disaster. The jealous Spaniards at St. Augustine showed signs of hostility. Against this expected trouble Oglethorpe had prepared by building forts in that direction. Finally, in 1739, war broke out between England and Spain, and Oglethorpe was made commander of the South Carolina and Georgia troops. With 1,000 men and some Indians he invaded Florida, but returned unsuccessful. In 1742 the Spaniards retaliated, and, with a strong land and naval force, threatened the Georgia colony with destruction. Disaster was averted by a stratagem employed by Oglethorpe, and peace was restored.

Indian Lands

By a compact between the national government and Georgia, made in 1802, they forever agreed, in consideration of the latter relinquishing her claim to the Mississippi territory, to extinguish, at the national expense, the Indian title to the lands occupied by them in Georgia, "whenever it could be peaceably done on reasonable terms." Since making that agreement, the national government had extinguished the Indian title to about 15,000,000 acres, and conveyed the same to the State of Georgia. There still remained 9,537,000 acres in possession of the Indians, of which 5,292,000 acres belonged to the Cherokees and the remainder to the Creek nation. In 1824 the State government became clamorous for the en-tire removal of the Indians from the commonwealth, and, at the solicitation of Governor Troup, President Monroe appointed two commissioners, selected by the governor, to make a treaty with the Creeks for the purchase of their lands. The latter were unwilling to sell and move away, for they had begun to enjoy the arts and comforts of civilization. They passed a law forbidding the sale of any of their lands, on pain of death. After the breaking up of the general council, a few of the chiefs violated this law by negotiating with the United States commissioners. By these chiefs, who were only a fraction of the leaders of the tribes, all the lands of the Creeks in Georgia were ceded to the United States. The treaty was ratified by the United States Senate, March 3, 1825. When information of these proceedings reached the Creeks, a secret council determined not to accept the treaty and to slay McIntosh, the chief of the party who had assented to it. He and another chief were shot, April 30. A new question now arose. Governor Troup contended that upon the ratification of the treaty the fee simple of the lands vested in Georgia. He took measures for a survey of the lands, under the authority of the legislature of Georgia, and to distribute them among the white inhabitants of the State. The remonstrances of the Creeks caused President Adams to appoint a special agent to investigate the matter, and General Gaines was sent with a competent force to prevent any disturbance. The agent reported that bad faith and corruption had marked the treaty, and that forty-nine-fiftieths of the Creeks were hostile to it. The President determined not to allow interference with the Indians until the next meeting of Congress. Troup determined, at first, to execute the treaty in spite of the President, but the firmness of the latter made the governor hesitate. A new negotiation was opened with the Creeks, and finally resulted in the cession of all the Creek lands in Georgia to the United States. By this new treaty the Creeks retained all their lands in Alabama, which had been ceded by a former treaty.